You might have heard that the Wikimedia Foundation and the National Portrait Gallery arehavinga bitof arow these days. At the core of the dispute lies the fact that in march an English wikipedia administrator by the name of Derrick Coetzee uploaded more than 3000 high resolution images of paintings held by the National Portrait Gallery to the Wikimedia Commons.

The images uploaded by were not simply taken from the NPG’s website and re-uploaded to the wikimedia commons, as the NPG does (and did) not provide high resolution images files on it’s website. While the NPG website only offers relatively low resolution images (see this page for a typical image provided by the NPG and this page for the high resolution version uploaded by Coetzee), Coetzee managed to use the website’s zomify feature (now disabled) in order to obtain the high resolution files and subsequently uploaded them to the Wikimedia Commons.

While the NPG does not dispute that the original paintings are in the public domain, it argues that Coetzee’s action violates a numer legal regimes that give the National Portrait Gallery the exclusive right to determine how these reproductions are distributed. According to an email send by the NPG’s law firm to Coetzee his actions constitute an Infringement of the NPG’s copyright in those images as well as an infringement of the NPG’s database right (in the database populated by these works). In addition the NPG argues that Coetzee’s actions constitute an unlawful circumvention of technical protection measures (even though zomify clearly states that zomify is not an image security system) and breach of contract. While all of these are serious allegations (the last one is a bit silly if you ask me) the current debate very much centers on the question if the National Portrait Gallery should have a copyright regarding these images. In a post on boingboing.net Cory Doctorow lays out why this is such a fundamental question:

In Britain, copyright law apparently gives a new copyright to someone who produces an image full of public domain material, effectively creating perpetual copyright for a museum that owns the original image, since they can decide who gets to copy it and then set terms on those copies that prevent them being treated as public domain.

Regardless of the fact that this is obviously problematic the general consensus seems to be that under British copyright law the NPG does indeed hold a copyright in the photographic reproductions (because the making of the reproductions of these paintings required a significant expenditure of labour) while under US law (the wikimedia foundation is based in the US) it does not.

So on one side we have the NPG claiming that it’s copyrights have been violated and that Coetzee/Wikimedia should therefore remove the high res-images from the Wikimedia Commons and on the other side we have Coetzee (backed by the Wikimedia Foundation, many wikipedians and Creative Commons) claiming that these images belong to the public domain and do not need to be removed. The wikimedia foundation’s Erik Möller has outlined this position in on the Wikimedia Foundation’s blog:

The Wikimedia Foundation has no reason to believe that the user in question has violated any applicable law, and we are exploring ways to support the user in the event that NPG follows up on its original threat. We are open to a compromise around the specific images, but our position on the legal status of these images is unlikely to change. Our position is shared by legal scholars and by many in the community of galleries, libraries, archives, and museums. In 2003, Peter Hirtle, 58th president of the Society of American Archivists, wrote:

“The conclusion we must draw is inescapable. Efforts to try to monopolize our holdings and generate revenue by exploiting our physical ownership of public domain works should not succeed. Such efforts make a mockery of the copyright balance between the interests of the copyright creator and the public.” [source]

Some in the international GLAM [pk: Galleries, Libraries, Archives and Museums] community have taken the opposite approach, and even gone so far to suggest that GLAM institutions should employ digitial watermarking and other Digital Restrictions Management (DRM) technologies to protect their alleged rights over public domain objects, and to enforce those rights aggressively.

The Wikimedia Foundation sympathizes with cultural institutions’ desire for revenue streams to help them maintain services for their audiences. And yet, if that revenue stream requires an institution to lock up and severely limit access to its educational materials, rather than allowing the materials to be freely available to everyone, that strikes us as counter to those institutions’ educational mission. It is hard to see a plausible argument that excluding public domain content from a free, non-profit encyclopedia serves any public interest whatsoever.

I completely agree with the position taken by the Wikimedia Foundation here. It should not be possible to monopolize public domain works by obtaining copyrights in simple (or even complicated) reproductions of these works. Once the copyrights in the original works have expired those who formerly held the copyright or those who happen to own the physical works should not have any exclusive right to determine what third parties can do with reproductions of these works. As far as i am concerned this is one of the fundamental principles of the public domain which cannot be pushed aside by museums in search of online business models.

However i have the feeling that this principle is not the only thing that should be considered in the current dispute. It is likely that in this particular case the National Portrait did not knowingly publish the high resolution photos of these portraits:

Assuming a certain level of technological ignorance on behalf of the NPG it is fairly safe to assume that they thought they where only making available 500 * 400 pixel images and allowed users of the website to see 500 * 400 px sections of the paintings in high resolution. Before Coetzee proved them otherwise the NPG probably never realized that this meant that the entire high-res files needed to be on a web-server somewhere.

Does the public domain status of the original paintings requires the NPG to make available the high-res photos? As far as i can see not. The public domain status of these paintings means that nobody has the right to control their reproduction and publication of reproductions anymore, but it does not mean that all reproductions of these pictures must be freely distributed. Just as i can take a photo of a public domain work and keep it for myself the NPG can decide to take these pictures and then keep them for whatever they please to do with them: There simply is no right of access to public domains works or their reproductions.

If you consider this it is a little bit easier to understand the position of the NPG. They never knowingly published the high-res versions of these images and all of a sudden they appear on Wikipedia and there does not seem to be a way to control their distribution anymore. At this point it is very much a theoretical question if the NPG has a right in these images or not because the images are out on the net and there is absolutely no way for anyone to regain control over them ever again (regardless of how the legal dispute will end).

However it is important to note that before these images got out onto the net the NPG did not try to control their distribution by asserting copyright but simply by not making them available, knowing (one assumes) that once they were available their copyright claims would be without much effect no matter how much these are backed by British law.

Given all of this i do think that it will be counterproductive to use this particular case in order to defend the principle that there should be no right of exclusive control over the distribution of reproductions of public domain works (as the blog post by Erik Möller implies). Instead this dispute is really about access control to these files.

If one is really interested in working on getting as many good quality reproductions of public domain works online then it is necessary to work with cultural heritage institutions by convincing them that making available these files without restrictions is in the best of their interest (as a number of Wikipedia volunteers argue in this excellent open letter).

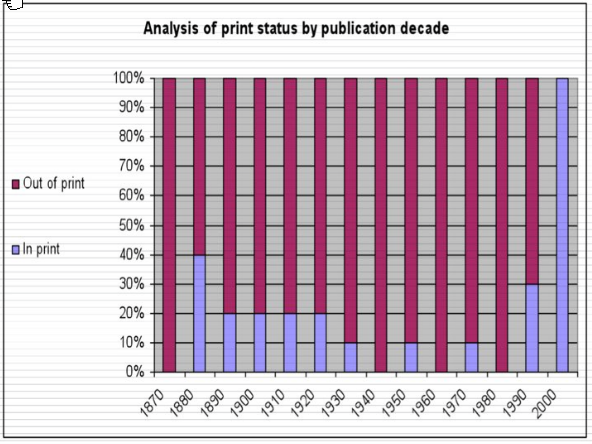

Working with cultural heritage institutions means that contributing to repositories of freely licensed and public domain works such as the Wikimedia Commens should always be based on conscious and voluntary decisions by those in a position to make material available. There is a growingnumberof examples of such behavior and it is probably only a question of time (and hard work on behalf of wikipedians) before more cultural heritage institutions recognize that making available their collections rather than keeping them locked away in search of marginal income from licensing[5] is more likely to strengthen their position in the digital environment.

It might very well be contra-productive to insist that the images obtained by Coetzee are not ‘protected’ by copyright as this is likely to make cultural heritage institutions feel even more threatened by public domain advocates. Instead this energy should be focussed on convincing cultural heritage institutions that it is in their best interest to to make their collections available as open as possible.