Hamiltonian cathedrals and the the Jeffersonian bazaar

Tumblr pointed me to a fascinating essay on the structure of our economic system. In ‘The American cloud‘ Venkatesh Rao explores the economic system of the United States by applying the much hyped cloud metaphor to the production, flows and consumption of goods. While it is not without flaws (reading it one might be tempted to believe that the USA are a self sufficient economy without any connections to the rest of the world) the essay provides an interesting perspective on our times.

At the core of his essay is Rao’s analysis of the US as an assemblage of Hamiltonian cathedrals and a Jeffersonian bazaar1:

Over the course of two centuries, the Hamiltonian makeover turned the isolationist, small-farmer America of Jefferson’s dreams into the epicentre of the technology-driven, planet-hacking project that we call globalisation. The visible signs of the makeover — I call them Hamiltonian cathedrals — are unprepossessing. Viewed from planes or interstate highways, grain silos, power plants, mines, landfills and railroad yards cannot compete visually with big sky and vast prairie. Nevertheless, the Hamiltonian makeover emptied out and transformed the interior of America into a technology-dominated space that still deserves the name heartland. Except that now the heart is an artificial one.

The makeover has been so psychologically disruptive that during the past century, the bulk of America’s cultural resources have been devoted to obscuring the realities of the cloud with simpler, more emotionally satisfying illusions. These constitute a theatre of pre-industrial community life primarily inspired, ironically enough, by Jefferson’s small-town visions. This theatre, which forms the backdrop of consumer lifestyles, can be found today inside every Whole Foods, Starbucks and mall in America. I call it the Jeffersonian bazaar.

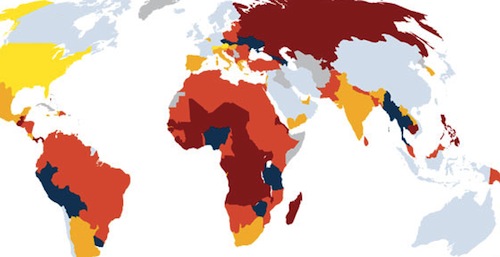

Structurally then, the American cloud is an assemblage of interconnected Hamiltonian cathedrals, artfully concealed behind a Jeffersonian bazaar. The spatial structure of this American edifice is surprisingly simple: a bicoastal surface that is mostly human-habitable bazaar, and a heartland that is mostly highly automated infrastructure cathedrals. In this world, the bazaars are the interiors of cities, forming a user-interface layer over the complex tangle of pipes, cables, dumpsters and loading docks that engineers call the last mile — the part that actually reaches the customer. The cities themselves are cathedrals crafted for human habitation out of steel and concrete. The bazaar is merely a thin fiction lining it. Between the two worlds there is a veil of manufactured normalcy — a studiously maintained aura of the small-town Jeffersonian ideal.

Assuming that this is analysis is (at least partially) true for the US it would be extremely interesting to map his idea of a bicoastal cloud surface onto Europe. Europe has a much more complicated geography than the US. We have no bicoastal population centres and the notion of heartland is difficult to establish in terms of geography. It might very well be the case that the geography of the European cloud is the inverse of what Rao describes: the human-habitable bazaar is found in the very centre while the feeder infrastructure can be found at the edges. More likely the european cloud would look like a accumulation of smaller clouds that take very different shapes, which is very illustrative of the growing pains that Europe is experiencing in trying to establish an single digital market.

Still it is clear that the separation between population centres and production and distribution centres that Rao highlights also exists over here. Rao ends his essay with a recommendation to the inhabitants of the Jeffersonian bazaar to venture out and explore the inside of the cloud:

To the Jeffersonian sensibility, Hamiltonian cathedrals are often little more than infrastructure porn. But to establish a direct, appreciative relationship with these technologies, unmediated by instrumental metaphors and currencies of interaction, you have to walk among them yourself. You have to experience train yards, landfills, radio-frequency ID-tagged seven-day cows and other such backstage oddities in the flesh.

This is something I can indeed recommend. My last, rather unexpected, experience with Hamiltonian cathedrals was a family vacation during which the vacation farm that we were staying on turned out to be a (indeed well obscured) industrial production facility for organic produce and diary complete with the above mentioned radio-frequency ID-tagged seven-day cows and semiautonomous, GPS guided robot tractors.

-

The terminology is obviously borrowed from Eric S. Raymond’s influential essay ‘The Cathedral and the Bazaar‘ that referred to two competing software development models. In Rao’s essay the the two models are not competing. Instead the bazaar can only exist by virtue of the cathedral. ↩︎