The text below is an adapted version of a text first published on the Kennisland website under the title “Time to move on: what we have done to improve copyright and access to cultural heritage”. Both texts are identical except for the last section. The version published here provides a more in depth reflection on the challenges ahead for digital policy making.

At the end of 2018 we will end our activities in the areas of copyright and cultural heritage. Kennisland has been working on these themes for over a decade but with the departure of Paul Keller, who has been leading these efforts, we have decided to focus our energies on innovation in Education, Cities and Care.

Internet access, civil society media and open content

Over the past fifteen years our efforts to create an open, knowledge driven society have taken a lot of different forms. Driven by the conviction of our founders that the technological revolution started by increasing access to the internet presented a lot of benefits to an open, inclusive and diverse society, we have worked on a wide range of projects that tried to leverage new technologies for social progress. This ranged from initiatives to improve internet access in disadvantaged communities like Digitale trapvelden (‘Digital playing fields’) to ideas ahead of their time like WIFI in de trein (‘WIFI in the train’).

The main catalyst in this area turned out to be the Digital Pioneers programme we ran from 2002 to 2010. Through this programme, designed to support small civil society organisations in setting up technology driven activities, we learned a lot about the potential and the challenges posed by the rapid digitisation of society. One of these challenges that we identified early on was how copyright and other forms of intellectual property were not evolving at the same speed as technology. This meant that technology enabled many activities that were in conflict with copyright and other laws. Therefore, in 2003, we started the project DISC (Domain Innovative Software and Content). Together with Waag Society we helped civil society organisations to leverage the power of open source software and open content. Our involvement in the emerging field of open content led us to set up Creative Commons Nederland, which Kennisland ran (together with the Institute for Information Law) from 2005 until 2018.

Working on the development and promoting the use of the Creative Commons licenses was our first step into the area of copyright, and brought us in contact with the copyright establishment. In the fall of 2007, after years of discussion and relationship building, we launched a pilot project with Buma/Stemra that for the first time allowed members of a collective management organisation (music authors) to share some of their works under an open license. This breakthrough later provided the basis for a flexible model that gives Buma/Stemra members more say over how their rights are managed.

Opening up cultural heritage

Also in 2007, Kennisland, together with the Dutch Institute for Sound and Vision, the EYE Filmmuseum and the National Archives embarked on an ambitious project to digitise the audio visual memory of the Netherlands. At the time, the project called Images for the Future was the largest digitisation project in Europe. Kennisland was responsible for the copyright, communication and business model aspects of the project. During the project (2007-2014) the project partners restored, preserved and digitised over 90,000 hours of video, 20,000 hours of film, 100,000 hours of audio and 2,500,000 photos.

As one of the initiators of Images for the Future our priority was to make sure that the digitised works would become available online under conditions that would allow reuse. With regards to this objective the project turned out to be less successful. Regretfully only a small percentage of the overall collections could be made available online, mainly because of unresolved copyright issues. Copyright turned out to be a much more thorny issue than we had expected. The original project plan was based on the assumption that copyright owners would provide permission for the digitised material to be used in return for payment. In reality, most of them did not, as the economic incentive never materialised.

However, we did manage to demonstrate the impact of making cultural heritage collections available under open licenses through platforms such as Open Images and the collaboration between the National Archives and Wikimedia. The latter illustrated that by sharing content on open platforms, institutions could reach new and larger audiences. These experiments around opening up collections for reuse became very influential for the nascent OpenGLAM movement. Realising that opening up GLAM collections (Galleries, Libraries, Archives, and Museums) was primarily a matter of working with public domain works and metadata, we worked with Creative Commons on developing the tools to facilitate this.

From 2009 onwards we also worked with collective rights management organisations on a number of pilot projects that explored the possibility of extended collective licensing as a mechanism to get more digitised cultural heritage available online. These projects proved to be successful and in response in 2013 cultural heritage institutions and collective rights management organisations joined forces (article available in Dutch only) to ask the Dutch legislator to provide a legal basis for extended collective licensing.

Based on our work in the cultural heritage sector we were an early partner of Europeana, the EU funded platform that brings together digitised cultural heritage from thousands of libraries, archives and museums across the EU. Europeana provided us with an opportunity to apply the lessons that we had learned in the Images for the Future project on a wider scale. Together with the Institute for Information Law and the Bibliothèque Nationale de Luxembourg we developed a licensing framework that ensures full reusability of the metadata aggregated by Europeana. It encourages institutions to make their collections available for reuse under open licenses. Today, ten years later, Europeana is the biggest aggregator of openly licensed cultural heritage resources, hosting more than twenty million freely licensed works. The success of the Europeana Licensing Framework, which focuses on clear rights information for end users promotes reuse, has inspired other cultural heritage aggregators around the globe, such as the Digital Public Library of America. Over the years of our collaboration Europeana has developed into one of the leading voices advocating for open access to cultural heritage and for the protection of the Public Domain. We are proud to have been a driver of this.

Fighting for better copyright rules in Europe

Since 2016 we have also worked with Europeana on making sure that the ongoing EU copyright reform will improve the ability of cultural heritage institutions to make more of their collections available online. While the reform process is not concluded, there are indications that the EU copyright reform package will finally provide a workable answer for the copyright problems faced by libraries, museums and archives engaged in large scale digitisation efforts.

But our fight for better copyright rules extends further than improving the position of cultural heritage institutions. As a founding member and core contributor of the International COMMUNIA Association we have been advocating for a more user-friendly and modern EU copyright framework. Together with our partners we have been advocating for Europe-wide rules that benefit educators and scientists, and encourage innovation and broad access to knowledge and culture. The fight for a more sensible copyright system remains an uphill battle. The legislative fight over the Digital Single Market Copyright Directive is still ongoing, and while it looks like we (together with our partners) have achieved substantial improvements for the cultural heritage and the educational sectors, it is also clear that copyright will continue to serve as a major barrier to unlocking the full potential of digital technologies for public institutions and civil society at large.

What’s next?

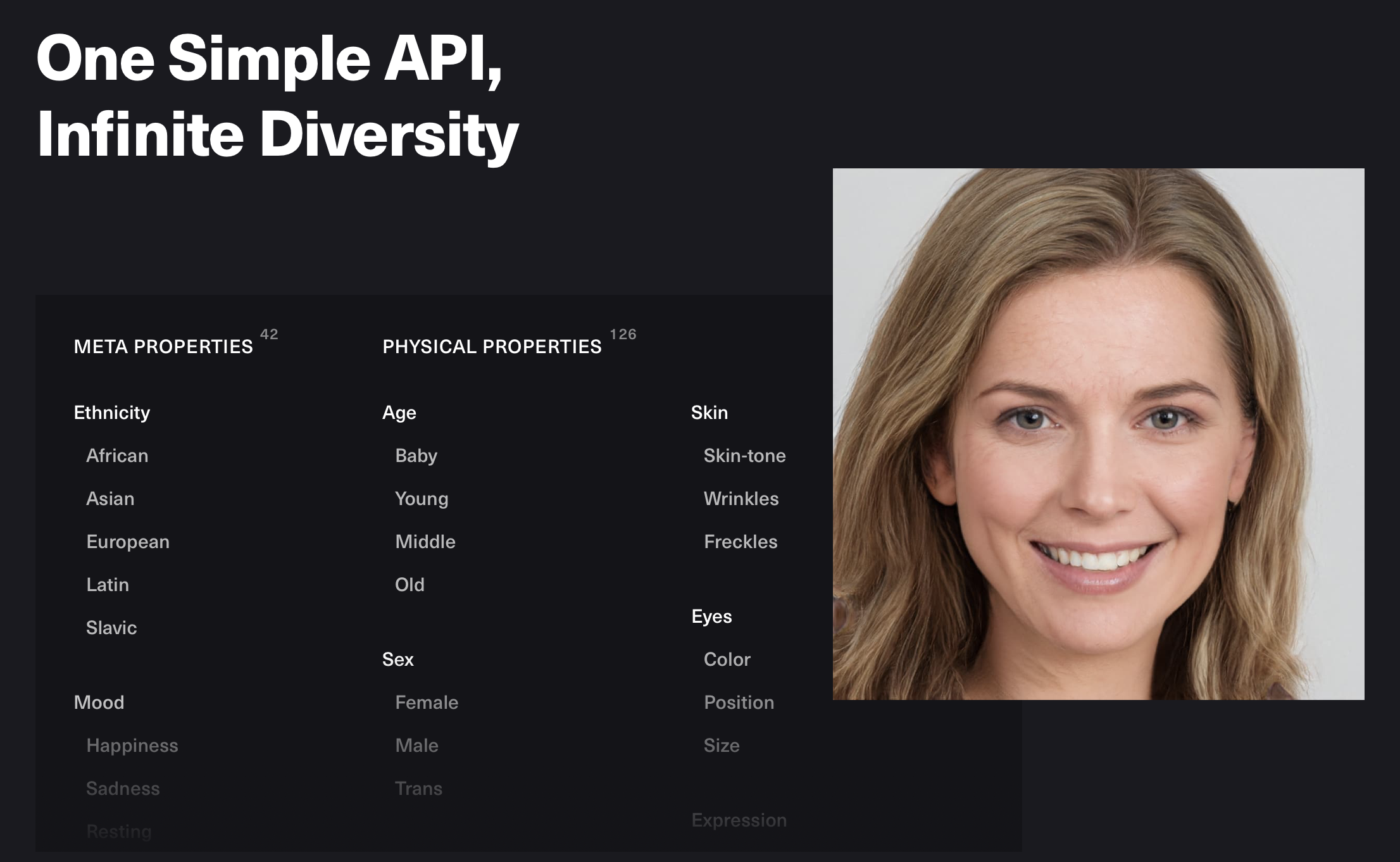

As we look back at almost fifteen years of activities, it is clear that many of the hopes that drove us to invest in these areas have failed to materialise. Instead of contributing to a more decentralised, democratic and equitable society, the digital revolution has brought us an increasingly centralised digital space that is undermining democracy and personal self-determination. At the same time, the rapid advancement of artificial intelligence is likely to raise an entirely new set of issues.

So why are we stopping our activities in this area when there is more urgency to act than ever?

We feel that after fifteen years we have exhausted our ability to intervene in meaningful ways. As an organisation that is entirely project-funded we need to find funders that are willing to pay for our interventions. Most funders that we have worked with prefer to fund activities/interventions that directly address a specific problem or issue that is relevant to their own mission (such as cultural heritage institutions for whom we have worked on copyright reform) or business (such as tech companies who have supported our copyright reform work). Such funding is usually tied to concrete opportunities or threats (like the ongoing EU copyright reform) and as such a lot of our work in the past years has been reactive to these kinds of threats and opportunities.

This has allowed us to change a lot of things for the better for the organisations and sectors that we have been working for. At the same time it is clear that we (as part of a bigger movement) have failed to counter the general trend towards an online space that is more and more dominated by a small number of powerful platforms that have built their dominance by extracting more an more of our private and public information. This situation poses a challenge for those like us who are part of the open movement. By advocating for opening up access to data, culture and information we have contributed to a favourable environment in which these platforms have come to dominate the online space.

If we want to reverse these developments and double down on our efforts to create a more decentralised, democratic and equitable society, there is a clear need for developing a more strategic, forward-looking policy agenda that furthers the policy objectives of the open movement.

Despite our long and successful track record in this field, Kennisland is no longer the place where this can happen. Both the funding model (dominated by relatively short-term project funding) and the relationship with our network of partners with whom we work on concrete social challenges (and who expect us to deliver concrete interventions in their immediate reality) drove us to the conclusion that Kennisland is no longer the place for long-term strategic policy work with an international focus. This is why I have decided to take these ambitions elsewhere.

Over the course of 2019 I hope to develop the foundations for a new entity that can be the host for these ambitions and that can become the basis for policies that rethink the digital environment in the light of what we have learned over the last decade and a half.