Using Creative Commons as a fig leaf

I have always had an unspecified strange feeling about Tribe of Noise. Tribe of Noise is an Amsterdam-based online music platform that allows musicians to upload and share their work as long as they agree to make it available under a Creative Commons Attribution ShareAlike license (CC-BY-SA). Simply put this license allows everybody to redistribute the songs on the platform, make remixes of them and redistribute these remixes under the same licensing terms. In all cases credit needs to be given to the original artist(s). It explicitly allows for commercial (re)use of the licensed works and it is one of the least restrictive Creative Commons licenses (and the license that has recently been chosen by a huge majority of wikipedia editors to apply to all text on wikipedia). I like this license.

I am writing this (rather long) text because I have come to the conclusion that the way Tribe of Noise uses this license is confusing to people contributing to the platform and can in the end be harmfull for the reputation of the Creative Commons Attribution ShareAlike license and the Creative Commons licensing model as a whole.

Even though i have endorsed Tribe of Noise back when it was launched (something i should have never done and which i am obviously retracting by writing this) the exclusive choice for the CC-BY-SA license made by Tribe of Noise never felt in line with the way the Tribe of Noise (TON) chooses to present itself: It is an aggressive start-up and the founder (and selfdeclared ‘Chief of Noise’) Hessel van Oorschot aggressively markets it as such. They have been quite successful in getting media attention and have known to attract a substantial number of artists to their platform (at the time of writing there are 5878 members). The platform is promoted to artists as a way to get in contact with commercial users of music.

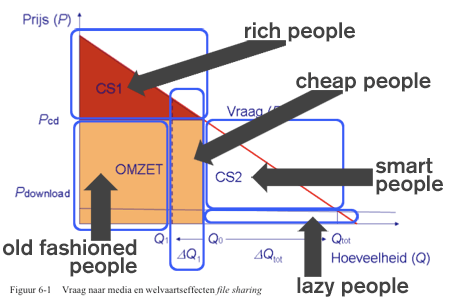

I have met with Hessel on a number of times in the past and among others i have invited him to the ‘Filesharing: Up or Down?‘ discussion that i organized at de Balie in Amsterdam in the wake of the Pirate Bay trail and the publication of the Ups and Downs study on the economic impacts of file sharing. That evening Hessel explained that one of the components of the Tribe of Noise business model is to license (for a fee one assumes) the music repertoire posted to Tribe of Noise to video hosting services so that they can use it in services like youtube’s audio-swap or offer the music to video makers that are looking for copyright un-encumbered music tracks to use in their videos.

However, such a business model is rather difficult to carry out based on the rights granted by the CC-BY-SA license. One of the key features of this license is that it requires derivative works of the original works to be licensed under the CC-BY-SA license as well (the share alike mechanism). This means, that every time a work licensed under a BY-SA license is integrated into another work (or the other way around) the resulting work needs to be distributed under a the CC-BY-SA license as well. If a video maker uses a short snippet of CC-BY-SA licensed music in a (long) video that is otherwise completely made by herself she needs to release the entire video under the CC-BY-SA license or she is in breach of the license (and thus infringing on the copyright of the musician in question)1. This means that CC-BY-SA licensed music is pretty much useless for purposes like sound-swap unless the provider of the service intends to force the video makers to use a CC-BY-SA license themselves.

Given this Tribe of Noise probably has a hard time selling the repertoire uploaded to the platform to video hosting services (at least as as long as you assume that they would base these transactions on the CC-BY-SA licenses granted by their uploaders2.

Back in April i did not really notice this contradiction. Tribe of Noise came back to my attention two weeks ago when i read about a Creative Amsterdam Award they had won at the ‘Creative Company Conference‘ in Amsterdam:

[…] The runner up, Tribe of Noise, was also given an honorary mention for their brilliant concept of music library in which creative commons licence (sic!) could be used for commercial purposes.

The fluffy language in the conference summary triggered my interest. What exactly is so brilliant about Tribe of Noise’s concept? Given the characteristics of the CC-BY-SA license explained above i failed to see how there could be a ‘brilliant concept of music library in which Creative Commons license could be used for commercial licenses’. Sure there are three CC licenses that allow for commercial use of the licensed works but it is hardly brilliant to allow people to upload content to your platform under one of them.

Given the limitations of the Attribution Share Alike license outlined above, one is inclined to assume that there are other parts to the business model that allow it to function and looking at the terms of use of Tribe of Noise it quickly becomes apparent that the business model of Tribe of Noise is not based on the rights granted by the uploaders via the Creative Commons licenses. Instead it relies on a much broader (and much less advertised) non-exclusive license granted to Tribe of Noise. Section 9 of the ToN terms of use, that you have to accept when you open a tribe of noise account contains these two sub-clauses:

- Licenses Granted by the User

9.1 If you upload any content to Tribe of Noise or post any content on the Website, you grant:

- a worldwide, nonexclusive, royalty-free, transferable license (with the right to sublicense) to Tribe of Noise for the use, reproduction, distribution, demonstration, making available to the public and performance of, and creation of derivative works from, that content in relation to the provision of the Services, and otherwise in relation to providing the Website and in relation to Tribe of Noise’s business operations, including the promotion and further distribution of all or part of the Website (and works derived from the Website or part thereof), in whatever media-format and through whichever media channel, now known or hereinafter invented;

- andto every user of your work on the Website the following Creative Commons license: CC 3.0 By – Share Alike.

What is of interest here is the first of these two clauses. It essentially grants Tribe of Noise the (non-exclusive) right to do whatever they want with the uploaded music. For example they can sell (non-exclusive) licenses to third parties without having to pass on parts of the revenues generated to the musicians that have uploaded the music. Also Tribe of Noise can allow third parties to do whatever they please with the music that has been uploaded to the platform (without having to require them to give attribution or redistribute derivative works under a CC license). In short, by uploading a work to Tribe of Noise the artist grants Tribe of Noise a very broad license that allows them to commercially exploit the work while not getting any right of compensation in return3. In the same section of the terms of use the uploaders also grant all users of the Tribe of Noise platform the right to use the uploaded works under the Creative Commons Attribution ShareAlike license.

This dual license grant is nothing that is specific to Tribe of Noise. Almost all web platforms ask more rights in the content uploaded by their users than what uploaders are willing to grant to the general public (see for example the terms of use of youtube which are very similar to those of ToN). Some services (jamendo, blip.tv) specifically ask for the right to grant commercial licenses to third parties or run ads in connection with the content but in return they promise to share the revenues generated through such transactions with the uploaders, which Tribe of Noise does not do.

Having users agree with terms of service that include such an unbalanced license grant can hardly be called a ‘brilliant business concept’ and definitely has noting to do with ‘using a Creative Commons use for commercial use’: Looking at the Terms of Use of Tribe of Noise one has to conclude that using a Creative Commons license has nothing to do with subsequent commercial exploitation of the uploaded works by Tribe of Noise as the commercial exploitation is enabled by the parallel license grant to Tribe of Noise.

Even worse, i get the impression that Tribe of Noise uses the Creative Commons licenses in order to hide the fact that they are indeed trying to obtain a much wider license grant from the members of the platform. Apart from the above quoted section of the Terms of Use there is no mention of the additional license grant to Tribe of Noise on their website. Certainly not in the FAQ or the more info movie aimed at musicians (the two places where one would expect to find information about what rights are granted by simply uploading a work). Instead, in the video with more information for artists, Hessel van Oorschot states that they have solved a ‘legal challenge of sharing music with companies’ by using the CC-BY-SA license4:

[…] sharing music with other musicians and companies around the globe and getting more attention that is a legal challenge. But we came up with a solution so let me know how it is done on tribe of noise: Sharing music online even for commercial purposes is legal!! with help from legal advisors laywers (sic!) and creative commons!! Creative Commons Attribution Share Alike 3.0 Unported5.

Of course Tribe of Noise is free to ask their users for whatever license grants they want (and one could imagine that some artists do not object to give away the right to commercial use in exchange for exposure of their work on Tribe of Noise). However one would assume that a site that states ‘Tribe of Noise means music and respect!‘ openly informs its uploaders what rights they are granting to the platform in exchange for being allowed to upload a work to the platform. Hiding such information in the legalese of the Terms of Service does not really show respect for the musicians using the platform.

First of all this is objectionable because it relies on the lame old trick of hiding stuff in the Terms of Use that one has to click though during a registration process and then using a CC licenses in order to imply that the site does respect everybody’s rights. However, the conduct of Tribe of Noise is also objectionable on a more profound level as it shows that the team behind Tribe of Noise apparently thinks that it is ok for them to make commercial deals with works authored and performed by other people without reimbursing them for such uses. While writing this i have asked Hessel van Oorschot if Tribe of Noise has a revenue sharing model in place and he has responded that they will certainly start working on a honest sharing mechanism. If such a revenue sharing mechanism gets introduced to the platform in the future that is certainly a step in the right direction but it does not aliveate my other point that Tribe of Noise is far from transparent when it comes to dealing with the copyrights of the members of the platform.

-

The cc licenses are quite specific about the use of music in combination with moving images. in section one of the licenses syncing of sound to moving image is explicitly defined to constitute a derivative work (and thus a trigger for the ShareAlike condition): ‘[…] For the avoidance of doubt, where the Work is a musical work, performance or phonogram, the synchronization of the Work in timed-relation with a moving image (“synching”) will be considered an Adaptation for the purpose of this License.’ ↩︎

-

Note that Tribe of Noise cannot sell licenses based on the CC-BY-SA license grant as none of the CC licenses allows for sublicensing. In theory ToN could be paid for curating, providing or making searchable of the content on the site but not for the CC license itself. ↩︎

-

This license grant ceases to exist once an uploader terminates the relationship with Tribe of Noise (by cancelling his account). However section 12 of the Terms of use ensure that licenses granted by Tribe of Noise to third parties remain valid after the termination. ↩︎

-

Transcription of the video at www.tribeofnoise.com/popup-make.php from 00:54 to 01:16 ↩︎

-

And apparently that is how they pitch their service to clueless juries at Creative Company Conferences and similar events. ↩︎