Brussels - a Manifesto: Towards the Capital of Europe

surf

‘Towards the west, the border is sharp because of natural conditions…’ [Brussels – a manifesto, p.27]

I have mentioned before that Bruxelles is one of my favorite cities in the world and certainly in Europe. This is in spite of (or rather because) the city is a mess: European institutions reside in buildings that most of the time look as if they have been randomly dropped from the sky and fact that the city is a nightmare to cycle in but a joy to be in a taxi since it has lots of tunnels (i ❤️ tunnels!).

In my perception Bruxelles with al its unfinishedness and it’s myriad of antagonisms has always felt like a proper capital of Europe, but i can understand why people are not perceiving it as such. With the European project under intensifying attack it is probably a really bad time to propose investing heavily into making Bruxelles a proper European capital, but that is exactly what the authors of the excellent ‘Brussels – a Manifesto: Towards the Capital of Europe’ proposed in their 2007 manifesto.

The whole manifest, from the observations on the borders of Europe that contain the above quote to architectural interventions proposed, really makes a lot of sense to me and i would love to see this realized sooner rather than later.

Of all the interventions proposed by the authors, one struck a particular chord in me: The Mundaneum complex that – according to the Manifesto’s authors – would come to house the European Central Library and a number of related Institutions. The Mundaneum gets his name from a rather fascinating post WWI attempt to build an institution that would hold all the worlds knowledge (a sort of pre-google/wikipedia if you will):

This project of culture and education in the west of Brussels refers to the Project that Paul Ortlet and Henri Lafontaine started in 1919: The creation of a Munadaneum in Brussels’ Cinquantenaire Area. The Ambition was to create a centre of centers, or a worlds database of knowledge – “a temple devoted to knowledge, education and fraternity among people”, ” a representation of the world and what it contains”. To be able to archive and this knowledge, Ortlet developed a standard classification system based on referential cards. This is the Universal Decimal Classification system that would simplify scientific research by establishing links between different forms and areas of knowledge. It is the first database , which also formed the basis for hypertext. Otlet’s and Lafontaine’s initiative was not an isolated case: At the same time Jorge Luis Borges’ imagined the Library of Babel as a place that contains “all the possible combinations of the twenty-odd orthographical symbols … the translation of every book in all languages, the interpolations of every book in all books”. [Brussels – a manifesto, p.152]

As someone spending a lot of my time working with Europeana, reading the proposal for the Mundaeum/European Central Library reminds me of the relatively sorry state of the European digitization effort. Europeana – it’s flagship and closest real world equivalent of the Manifesto’s Europeana Central Library – currently consists of a website that provides information about 20M works, many of which are only accessible in low-quality to online users. This stands in sharp contrast this with the – entirely fictional – description of the European Central Library from the manifesto:

The Central Library, cooperating with national libraries, provides the links, translations and information to be elaborated and processed. Books, cinema, newspapers, music, etcetera would be digitized and saved in one place; 260.000.000 items now stored on the shelves of 25 national libraries in 43 different languages would all be organized with the UDC system that Paul Ortlet developed. [Brussels – a manifesto, p.152]

Reading the above, it strikes me that one of the things that Europeana is missing most is an offline presence like the proposed Mundaneum :

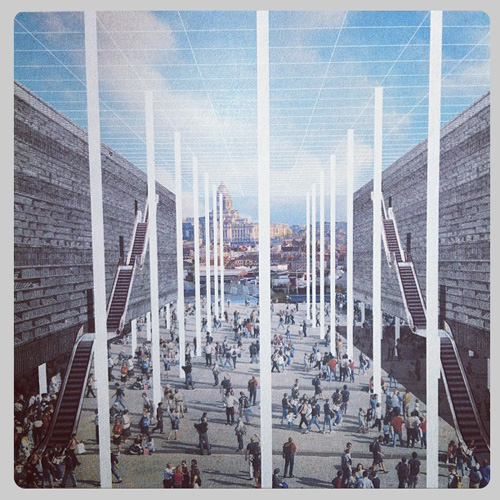

European Central Library

This is what europeana should be looking like today [Brussels – a manifesto, p.157]

bonus: The proposed location for the Mundaneum is right next to the spot where i took this picture back in 2000 or so…

update [14.3.12]: The folks at google have discovered the mundane as well. they have also produced a nice little video honoring Ortlet as ‘the man who dreamt the internet‘.